National Native American Heritage Month: Centering African-Native Americans.

Via @Melaninmvskoke on instagram

Guest Blog by Dr. Jeffery U. Darensbourg

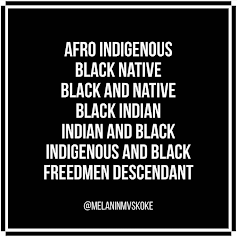

November is National Native American Heritage Month, a time to celebrate Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, a time to learn and reflect on the original inhabitants of this continent. Owing no doubt to my own ethnic heritage and work (I am a Louisiana Creole and a member of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation) I’d like to reflect on persons who are of both African and Native American ancestry. African-Native Americans, sometimes known by terms such as “Black Indians,” exist, and have existed as long as Indigenous Peoples of the Americas and Indigenous Peoples of Africa have shared space in the Western Hemisphere. The existence of such peoples, and the historical legacies of racism, enslavement, and miscategorization surrounding us has been the subject of much in the way of scholarship and the arts in recent decades. We exist, and some of us have been writing about it on our own terms.

Afro-Indigeneity

Seminal scholarship about African-Native Americans was done by the late Jack D. Forbes, and the tradition has continued across many publications, including an excellent single volume source from the National Museum of the American Indian, indiVisible: African-Native American Lives in the Americas, edited by Gabrielle Tayac. African-Native Americans include many well known individuals, people who have shaped the culture of the United States of America and the larger world.

In school we learn of Crispus Attucks, an early casualty of the fight for Independence from the British Crown who perished at the Boston Massacre. When studying him, we learn that he was African American, but we do not usually learn that he was also Native American, that his mother was of the Natick Nation. In 2020, at an event marking the 250th anniversary of the death of Attucks at the hands of British troops, a group of protestors, including Jean Luc Pierite of the North American Indian Center of Boston, a member of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana, called to mind Attucks as a symbol of police violence against People of Color: African, Native, and otherwise. While law enforcement violence towards African Americans has received much attention in recent years, and deservedly so, studies from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention have indicated that Native Americans are the population most likely to be shot by police in the United States.

Intersectionality and Erasure

I am a guitarist, and so I cannot help but point out a few musicians who are African-Native Americans, including the utterly peerless Cherokee guitarist Jimi Hendrix, whose Indigenous heritage and identity is discussed by his sister in Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World, a pioneering 2017 documentary placing Indigenous People at the center of rock and roll. Hendrix walked in the footsteps of other African-Native American guitarists such as Delta blues pioneer Charley Patton (1891-1934), a Choctaw and Cherokee man from Mississippi, and a personal favorite, Scrapper Blackwell (1903-1962), a Cherokee fellow from South Carolina.

Here is a Spotify playlist of some African-Native American musicians I’ve curated for this post.

Why isn’t the Native ancestry of some of the above better known? Perhaps it’s that in the United States there is often a prejudice such that African blood is seen as a contaminant, whereby its presence negates all other ancestry. This is seen in so-called “one-drop rules,” a tool of segregation whereby individuals with any African ancestry were legally classified as African American only. The attitudes reflected in such legislation persist. As such, some people cannot see mixed ethnicity individuals in our wholeness, as people existing between sharp divisions of race, divisions deeply rooted in ideologies of white supremacy.

I am part of a mixed population known as Louisiana Creoles. We are a mixture of Europeans (mostly French and Spanish), West African, and Indigenous ancestry. That definition is too simple, and so are most others. We are a group of people, though, and as a group of people we have those ancestries, and we look every imaginable way related to our lineages. Some of us have close relationships with our Indigenous backgrounds, something aptly documented by the work of my tribal cousin Andrew Jolivétte. There are some historical tribes in Louisiana whose identity has been “Creolized,” as Andrew calls it. These are tribes whose members tend to be Creole people living out their Indigenous identities as mixed-ethnicity persons. Such tribes can have difficulty with the federal recognition process, especially as these tribes often have to contend not only with present racism against African-Native Americans, but also historical legacies in Louisiana of deliberate miscategorization in documents.

Unrecognized Stories

Recently Hali Dardar, a member of the United Houma Nation, and I received a grant to document members of non-federally recognized Indigenous Nations in Louisiana via a series of interviews. Happily, another Houma citizen, Ida Aronson, was taken onto the project as well, the results were a series of interviews, artwork, and photographs in which members of these groups, including many instances in which African-Native Identity was discussed. Our project, Unrecognized Stories, is an attempt to provide a space for people to tell others about themselves, about their identity, from their own point of view. Of particular note in this regard are the three interviews below. One is with Cougar Goodbear, leader of a group of Lipan Apache whose ancestors were sold into slavery in Louisiana and settled in St. Martin Parish after gaining freedom. We also recorded interviews with Colette Pichon Battle, a Creole attorney who discussed her family’s mixed identity, as well as Scierra LeGarde, a Bayou Lacombe Choctaw who is also Creole, and whose people were the subject of an entire monograph by a researcher on behalf of the United States Government a century ago, and who still do not have federal recognition.

Scierra LeGarde - Dancing, Persistence, Environment - YouTube

Chief Cougar Goodbear - Art, Roots, Ceremony - YouTube

Colette Pichon Battle - Water, Land, and Law - YouTube

It is my hope that you will learn about African-Native Americans, and that you will recognize that mixed ethnicity people exist, exist as whole people, with identities that cross over rigidly defined categories. I hope you will listen to the interviews above, which contain much in the way of thoughtful reflection. I also hope you will enjoy the music linked here. As we say in Ishakkoy, hiwew, thanks for reading.

About the Author

Writer, public speaker, researcher, zinemaker, and provacateur Jeffery U. Darensbourg, Ph.D., is member of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation of Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas. He is the founder and Editor-Who's-not-a-Chief of Bulbancha Is Still a Place: Indigenous Culture from New Orleans. Recently a writer and resident at Tulane University's A Studio in the Woods and a Monroe Fellow of New Orleans Center for the Gulf South at Tulane, Jeffery is working on a book length study of the Atakapa-Ishak of Southwest Louisiana. Dr. Darensbourg was quintessential in helping Beloved Community craft the Indigenous Land Acknowledgement we use at the the beginning of every facilitation, and continues to work with the organization to create sustainable partnerships with Bulbancha indigenous communities.

Dr. Jeffery U. Darensbourg

jefferydarensbourg@gmail.com | 225.505.3192